Last Seen Online [Talk]

By:

Ellen LapperBroadcast on:

Sep 20, 2020

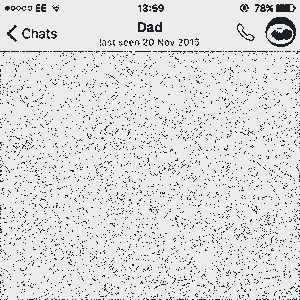

In a time in which death is moving rapidly online (funeral streaming services during COVID-19, #RIPcelebrity hashtags trending on Twitter), we all have to face the question of what happens to our own digital afterlives, as well as those of our loved ones. Digital death is the ultimate clash of familiar human concepts of time with the ubiquitous computational time. Facebook and Instagram offer possibilities for “immortalisation” with a memorialised profile, Twitter only offers deactivation. The need to humanise algorithms is now vital; Facebook friend suggestions and birthday reminders of the deceased aren’t exactly perceptive. Cue capitalising companies offering to use AI to analyse activity and learn how to post for you after death. But are their promises really immortal? And if, as predictions suggest, the dead soon outnumber the living on Facebook, who’s going to pay for their upkeep? Dead people aren’t very useful consumers; they won’t be clicking on those targeted ads. So what happens to the feedback loop when it’s the deceased generating the data? And who ultimately owns this data? This research began from a personal note following the death of my father. Unprepared, I found myself clinging to the digital traces that remained of him. Using participatory methods, I conversed with Facebook users who were vocalising a death on the platform. This research explores the presentation of the self across public platforms and negotiates a physical absence in light of a persistence digital presence. Anthropological research into death and grief online faces new challenges: omnipresent online traces, ethical algorithms, data storage and an online field-site. Essentially death is an inevitable accompaniment to our existence and, like in other fields, we are constantly catching up with technology and surrendering our control; this is no exception, perhaps we just need to acclimatise quicker than the companies.